The full picture

You don't need any of this to participate. But if you want to understand the research foundations, here they are.

Lian Passmore — Project Rise

Samoan and NZ European. Mum of five. Based in Whangārei. 14 years in learning design. Taught herself to build.

Supervisor: Felix Scholz.

Main Research Question

How might we design ethical conversational AI for vulnerable interactions using Māori and Pasifika values?

Project Rise began with a simple question: why do the people who most need to be heard find it hardest to give feedback?

See more Show less

Sub-questions (Kiri Dell's compass framework)

- Kei raro (Foundations): What systemic barriers silence vulnerable voices in digital spaces?

- Kei mua (Values): How do Māori and Pasifika values translate into AI design decisions?

- Kei runga (Purpose): What purpose does ethical AI serve for vulnerable communities?

- Kei roto (Agency): How do we protect data sovereignty, safety, and dignity?

- Kei waho (Innovation): How do we develop this ethically with cultural governance?

Relational Insights for Systemic Empowerment

The research started with feedback systems — the surveys, review platforms, and forms that businesses use to hear from their customers. What became clear early on was that the problem isn't verification or technology. The problem is relationality. Current digital systems are transactional by design. They extract information without building trust, and the people most affected by poor services — Māori, Pasifika, disabled, and digitally excluded communities — are the ones least likely to engage with them.

Project Rise explores how conversational AI can transform these transactional interactions into relational, trust-building experiences. The research is grounded in three core values drawn from Māori and Pasifika worldviews:

- Vā — the sacred relational space between people

- Utu Tūturu — enduring collective reciprocity

- Mana Motuhake — absolute data sovereignty

The guiding whakataukī is Mā te kōrero ka ora — through conversation, there is life.

The case study: Ray

Ray didn't start as a research project. It started at home.

Lian built a conversational AI agent for herself and her husband — a tool to help them talk through the stuff that's hard to talk through. Patterns they kept falling into. Conversations that went sideways. The things you know you need to say but can't quite find the words for.

It worked. Not perfectly, not like therapy, but enough that something shifted. They were hearing each other differently. And Lian found herself at an intersection she hadn't expected — sitting with a tool she'd built in her living room, realising it had just held a genuinely vulnerable conversation, and wondering: could this be used safely by other people? What would it take to do this ethically? And what happens when AI enters spaces that are this personal?

That's how a homemade app became a case study for a master's thesis.

Ray is now a voice-based AI relationship coach — the primary case study for Project Rise. Relationships sit at the intersection of identity, emotion, whānau, mana, and trust. They are among the most vulnerable conversations a person can have. The logic is simple: if conversational AI can be designed to work ethically and safely in this context, it can work anywhere.

Ray works with any relationship — romantic, whānau, friendships, workplace, or your relationship with yourself. It helps people recognise patterns, see dynamics they might be stuck in, and make decisions with more clarity. It is coaching, not therapy. It is transparent about being AI. And it is built on the same values that underpin all of Project Rise.

Ray is currently in a two-week pilot (February 12–26, 2026) with participants testing whether the approach delivers on its promises: safety, cultural grounding, and genuine usefulness in vulnerable conversations.

Why this matters

Most AI is designed for efficiency. Project Rise asks whether AI can be designed for care. The research contributes a framework that does not yet exist — one that centres Indigenous values in conversational AI design, not as decoration but as architecture. If the pilot shows that Ray is safe, helpful, and culturally grounded, the principles behind it become a blueprint for any conversational AI operating in vulnerable spaces.

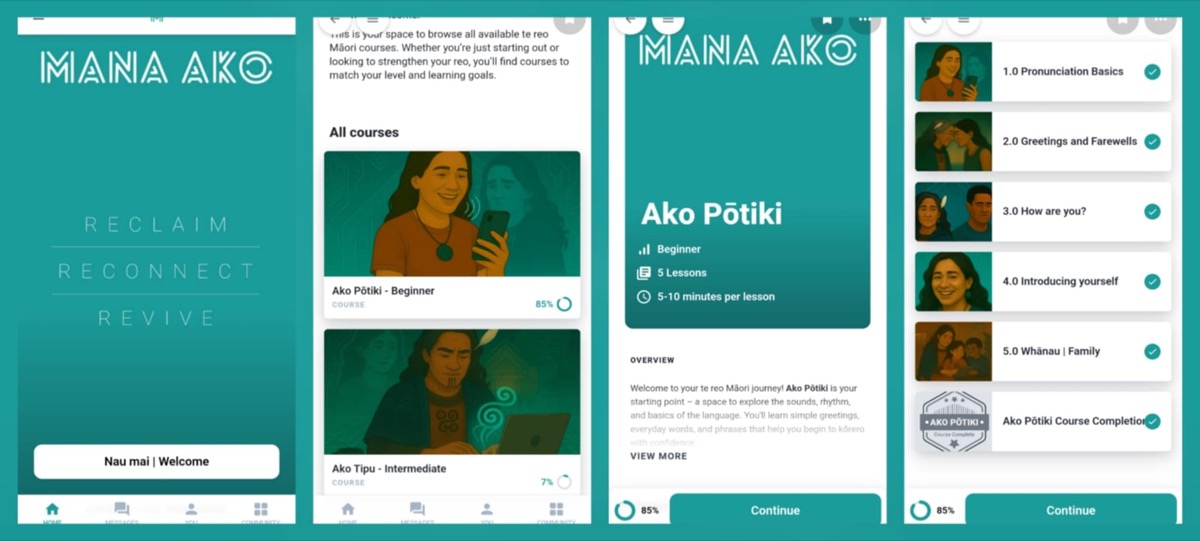

Lee Palamo — Mana Ako

Learning Experience Lead at Northpower. South Auckland roots. Her project explores conversational AI for te reo Māori learners — creating space to practise without fear or shame.

Supervisor: Paula Gair.

Main Research Question

How might conversational AI support te reo Māori learners with a culturally grounded, emotionally safe experience?

Mana Ako is Lee's te reo Māori learning app — a space to practise without fear or shame. The name speaks to the mana in learning — honouring the courage it takes to begin, and the dignity every learner deserves along the way.

See more Show less

Sub-questions

- How might AI help foster a safe, non-judgemental community of practice where learners can build confidence, connect with others, and explore te reo Māori together?

- What impact does using a conversational AI have on learners' confidence, motivation, and willingness to kōrero in te reo Māori?

- How might personalisation through AI and interactive learning design support motivation and a deeper connection to te reo Māori?

Research in Motion

Mana Ako sits within Lee's Master's research programme exploring conversational AI in Indigenous language revitalisation.

At the centre of this work is a conversational AI kōrero agent called Oriwa, named after Lee's nan. Naming her after her grandmother keeps this grounded in whakapapa. This is not abstract technology — it is personal.

This research is not about proving that AI works. It is about asking whether it should, how it might, and where the limits sit.

What happens when conversational AI enters the emotional space of learning te reo Māori?

Many adult learners describe hesitation, whakamā, or anxiety about speaking out loud. Mana Ako explores whether practising privately with Oriwa, in your own time and space, might support confidence, or whether it risks creating something unintended. This research remains open to both possibilities.

Areas being explored

Emotional Safety

Does practising in your own time and space reduce the fear of getting it wrong, or does it reinforce isolation from community-based learning?

Cultural Grounding

What does it mean to design conversational AI through kaupapa Māori principles rather than layering culture on top of technology? How do dialect, tikanga, and relational accountability shape design boundaries, especially beginning within Ngāti Awa?

Responsibility and Limits

AI makes mistakes. It reflects bias. It simplifies complexity. Part of this research is making those limitations visible rather than hiding them. Where are the ethical red lines? Where should AI not be used?

Why the wānanga matters

This wānanga is part of the research itself. It is a space to critically examine:

- What "non-judgemental" really means

- Whether AI like Oriwa can hold mana safely

- What risks sit beneath convenience

- Whether conversational AI belongs in this space at all

Mana Ako begins within Ngāti Awa to stay grounded and accountable before any consideration of broader scalability across dialects. This is research in motion, not a finished product. The direction it takes will be shaped by collective whakaaro.

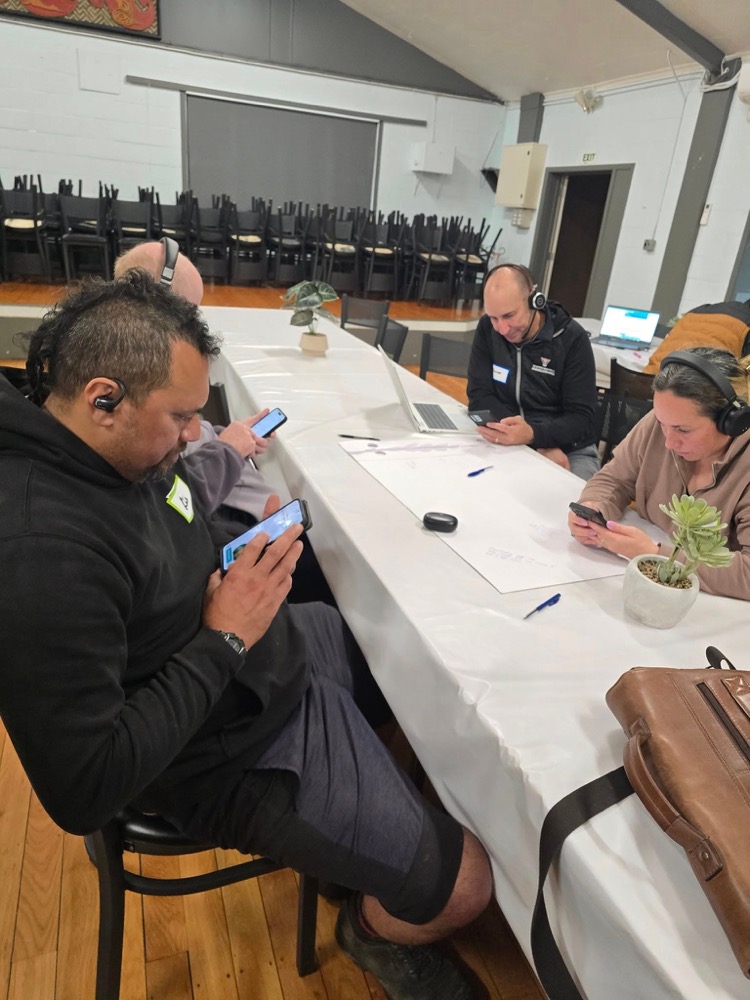

Testing the app in a real workshop setting:

Why we're working together

Lian and Lee go way back. They first crossed paths when Lian was four or five — Lee went to school with her older sister. Fast forward twenty years and they found each other again as Learning Designers, battling it out for top spot at eLearning conference competitions year after year. That rivalry turned into a partnership when they worked together at Northpower for three to four years in the People and Capability team, and stood alongside each other as Kaitiaki in the peer support network.

Now they are doing their master's side by side — and the research landed in the same space. The people using Lee's app are scared — scared of making mistakes, of being judged, of not being Māori enough. The people using Lian's app are scared too — scared of being vulnerable, of opening up to a machine. The emotional terrain is the same. The cultural questions are the same. They are stronger exploring them together.

The gap

There's research on data sovereignty. Research on shame in language learning. Research on AI and Indigenous communities. Nobody has woven them together to ask: what happens when AI holds a conversation that touches something sacred?

Methodology

Participatory Action Research. You're a co-researcher, not a subject. Both projects operate under kaupapa Māori research principles with cultural supervision.

Our tools and their limitations

We believe in being upfront about our tools and their limitations. This research uses:

- ElevenLabs (US-based) for the conversational AI voice agent

- Supabase (hosted in Sydney, Australia) for registration data, with row-level security

- Zoom for the live wānanga

We do not own or control the AI infrastructure. The voice platform is built by a company based outside Aotearoa, governed by US law, with data stored on US servers. We have opted out of our data being used for AI model training, but ElevenLabs' Terms of Service include a broad license on data processed through their platform.

We chose these tools because building our own voice AI infrastructure was beyond our resources as two master's students working across Aotearoa. Te Hiku Media — who built their own speech recognition for te reo Māori — have shown what full sovereignty looks like. We are not there. We are honest about that, and the tension between our principles and our tools is part of what this research examines.

Want to be part of it?

Four ways to take part — pick whatever feels right.